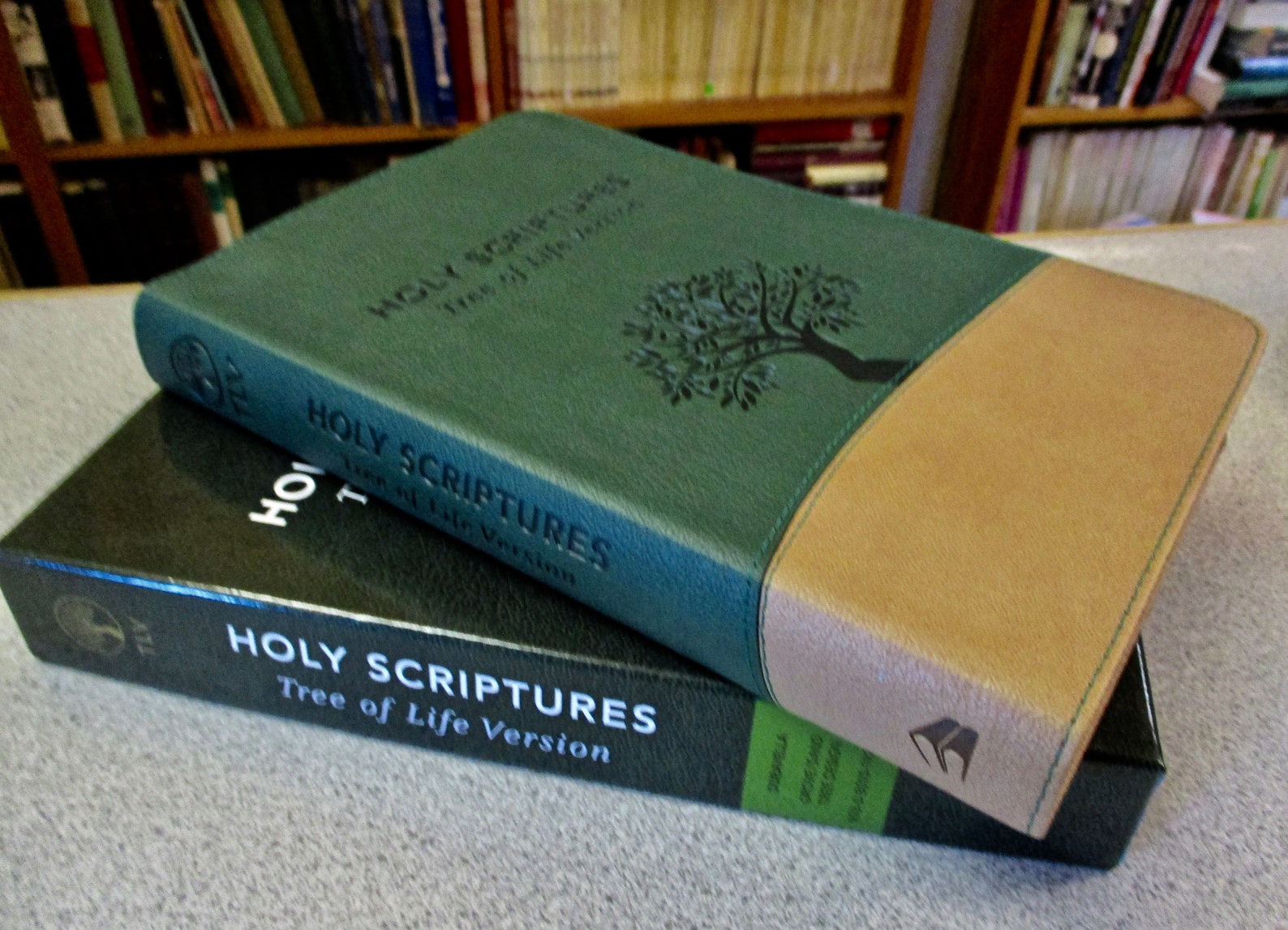

Carefully, consciously, sparingly - but used,” he said. “We did not bring it here to sit in some museum. Senebato has no intention of donating the book for academic purposes. According to family tradition, the book was handed down to an ancestor who lived 300 years ago. But family members believe it is older still. Scholars at Israel’s National Library who examined the Meshiha family’s book at the family’s request believe it is about 200 years old. It included songs, rabbinical interpretations and stories in Amharic and Tigrinya. The Meshiha family’s copy attests to the unwritten liturgy that has evolved around the Orit over the centuries. “These cultural treasures are facing extinction,” Dalit Rom-Shiloni, the researcher leading the program, said at the time. Recognizing the paucity of data about the Orit and the danger that knowledge about it could disappear after the immigration of nearly all of Ethiopia’s Jews to Israel, Tel Aviv University opened the world’s first academic program focused on the holy scriptures of Ethiopian Jews in 2020. The largely oral transmission of the Orit has varied greatly between regions and even communities in Ethiopia. It’s a remarkable reminder of how ancient Ethiopian Jewry is: Some believe it to be more than 2,600 years old.Įthiopian Jews brought a few precious Orit books with them when they immigrated to Israel beginning in the 1980s, but each document offers a distinct and partial representation of its congregation’s history, devoutness and rabbinical traditions. It is one of just a handful texts in Israel of the Orit, an Ethiopian variant of the Hebrew Bible that predates the advent of that standardized text.

The book is significant to far more than just Askabo Meshiha’s extended family. “But we all felt like it was a piece of our family, returned to it, when we took it in our hands.” “I was too young to remember it,” said Senebato. The older cousins remember the book from their time in Ethiopia, where they lived in the village of Vinerb near Lake Tana, about 250 miles northeast of Addis Ababa. “This book has been in my family long before any of Ethiopia’s laws were written,” he said. Senebato said he is unconcerned that he broke Ethiopia’s laws against taking historically significant artifacts out of the country, though he declined to name the priest who released the book to avoid implicating someone who remains there. “I was overcome with pride and excitement when the book was read, and when the name of my ancestor was found,” Senebato said. He found scribbled on one page of the book the name of Senebato’s great-great-grandfather, Erqshen Sequin. Last week, the book was used in prayer, probably for the first time in at least 34 years, at the home of Mentasnut Memo, a kes who lives in Kiryat Gat in southern Israel. But the book’s significance remained easy to identify: Among the multiple types and colors of ink, some segments are written in red - a way of signifying that a kes, the Amharic-language word for a rabbi, had made additions to the original.Įven speakers of Amharic typically cannot read or communicate in Ge’ez, which is decipherable only to a dwindling group of spiritual leaders of Ethiopian Jewry, who mostly now live in Israel.Ī view of the Orit book that Ayanawo Ferada Senebato and his family retrieved in Ethiopia and smuggled to Israel in February 2022. Together, they negotiated the deal and wrapped the fragile book in an Israeli flag they had brought.ĭozens of square parchment pages measuring 11-by-11 inches had fallen out of the binding, and others were barely attached. Senebato boarded a plane to Ethiopia with his older cousins: Getnat Eshato Selam, a father of six who lives in Lod and works at Ben Gurion Airport, where he and his family landed in 1991, and David Malsa Makuria, who lives in Ashkelon and works at a water sanitation company. But now, pressed for cash, he agreed to part with it for $1,200. In previous negotiations, the priest had demanded more than $10,000 to release the book. Senebato and two of his cousins made their way to northern Ethiopia earlier this year amid the civil war raging there, acting on a tip from Ethiopia-based friends of their grandmother: The Christian priest who had possessed the book for years had been arrested and needed money to get out of jail.

“When I posted the picture of the book in the family WhatsApp group, people went nuts, it’s like a long-lost relative had returned,” said Ayanawo Ferada Senebato, Mashiha’s 43-year-old grandson and a journalist and activist promoting causes linked to Ethiopian Israelis. The family now hopes to restore the book and use it to strengthen their community’s fading identity. In March, an unusual set of circumstances finally allowed the family to be reunited with the document, a rare but tangible relic from the rich traditions of one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)